AI in military training:

legal boundaries of simulation and decision making in the era of autonomous systems

The soldier is not in the dusty terrain of the Middle East or in a broken-down city in Eastern Europe. It sits in an air-conditioned room thousands of miles from any real conflict. He is wearing a virtual reality headset and his senses are fully absorbed in a hyper-realistic scenario. He is in a so-called Synthetic Training Environment (STE), a digital twin of the real battlefield, powered by artificial intelligence. And the legal aspects are discussed in this article.

Author of the article: ARROWS (JUDr. Jakub Dohnal, Ph.D., LL.M., office@arws.cz, +420 245 007 740)

.jpg)

The AI is adjusting the simulation in real time, learning from its responses and presenting it with increasingly difficult challenges. It now faces an ambiguous situation: in a busy marketplace, a small group of people in civilian clothes approaches a protected convoy. Some of them are carrying objects that could be weapons, but could just as easily be tools or parts of goods. The AI, which has analyzed thousands of hours of footage from past encounters, identifies a pattern in their behavior that is 87% likely to be consistent with preparation for an attack. A synthetic voice in her ear says, "Threat detected. Target disarming advised. Make a decision." She has only a split second.

This scenario is no longer science fiction. It's contemporary military training. And it is here, at the intersection of code and human decision-making, that a whole new category of legal risk is born. If a soldier learns from this training to neutralize similar targets without 100% positive identification and then attacks innocent civilians in a real conflict, who will be legally responsible? Will it be her because she acted on her best training? Her commander who authorized the use of this simulation platform? Or your company, the technology leader whose programmers and data scientists created the algorithm that became the silent instructor in life-and-death decisions?

This article aims to demystify this complex and rapidly evolving legal landscape. It is intended for leaders in technology, the defense industry, and government agencies to provide a clear framework for understanding and mitigating these unprecedented risks. At ARROWS, we specialize in these issues and stand ready to be your expert guide in this new, uncharted territory.

Synthetic Reality: The Promise and Pitfalls of Artificial Intelligence in Military Training

The revolution in the military is not only taking place in the field of weapon systems, but especially in the field of training. Modern militaries are faced with the need to train for complex scenarios such as fighting in densely populated urban agglomerations or operations across multiple domains (ground, air, cyberspace) that are extremely costly, dangerous and often impossible to physically replicate. The technological answer to this challenge is called the Synthetic Training Environment (STE). It is a convergence of Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), cloud technologies and most importantly, Artificial Intelligence, which creates immersive, scalable and adaptive training scenarios.

The benefits are undeniable. AI enables the processing of massive amounts of data in real time, providing commanders with unprecedented situational awareness and the ability to "fight at the speed of the machine." Soldiers can repeatedly train decision-making processes in realistic conditions that mimic not only the physical but also the psychological aspects of combat, including stress and cognitive load. Platforms like One World Terrain (OWT) can create accurate digital replicas of any location on Earth, while adaptive AI adversaries learn from soldiers' tactics and constantly change their behavior, forcing them to be constantly creative and adaptable.

But this technological leap has created a deep legal divide. While engineers are pushing the boundaries of what is possible, international law, designed for an era of human decisions, is lagging behind. The so-called "accountability gap" is emerging: a situation where an autonomous system causes damage that would be a war crime if committed by a human, but no specific individual bears direct criminal responsibility because of the lack of intentional culpability (mens rea). For government agencies and their private partners, this poses significant, often hidden, legal and financial risks that can jeopardize not only specific projects but also the company's entire reputation.

The reason is both simple and fundamental. The desire to maximize the realism and "psychological fidelity" of training has direct legal implications. The more perfectly a simulation mimics reality, the more likely its internal logic and possible biases will be seen as a direct form of 'instruction' and 'training' within the meaning of international humanitarian law (IHL). Under the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols, states have an obligation to ensure that their armed forces are properly trained in this law. Thus, once AI simulation becomes a major tool for teaching tactical decision-making, it becomes itself a means of fulfilling (or violating) this international obligation of the state. AI thus transforms from a mere "tool" into a "legal instructor." And any flaw in its "teaching" - algorithmic bias, for example - is no longer just a technical deficiency, but a potential violation of a state's international legal obligations.

At ARROWS, we work closely with the technology leaders and defense contractors who are at the forefront of this development. Our job is not only to respond to current legislation, but to proactively model future legal risks and help clients design technologies and business models that are resilient to the inevitable changes in international law.

"Preparing for battle" in the eyes of the law: where does training end and responsibility begin?

One of the key questions our clients ask is whether training using AI simulations can be considered "preparing for combat" in the eyes of international law. The answer to this question has major implications for the scope of legal liability. Many mistakenly believe that all military activities are protected by the broad shield of so-called "combat immunity". This doctrine does exist and provides that a state cannot be sued for mistakes made by its soldiers "in the heat of battle." This protects decisions made under extreme pressure and in imminent danger to life.

However, the precedent-setting judgment of the British Supreme Court in Smith and Others v Ministry of Defence was a major breakthrough. In this case, the Court held that combat immunity does not apply to decisions made during the planning, equipment acquisition and training phases. This distinction is absolutely crucial. It means that decisions about what system to acquire, how to design its software, and how to train soldiers on it are not protected by immunity and are subject to legal review. They can become the basis for a negligence or breach of duty of care claim.

This principle opens the door to liability that begins long before the first shot is fired on the battlefield. It shifts the focus from the soldier's actions in the field to decisions made in the offices of defense ministries and in the development centers of technology companies.

This view is further reinforced by the positive obligations of states under international humanitarian law. States have a duty of 'due diligence', which means that they must take all reasonable measures to prevent violations of IHL. This obligation does not begin with the outbreak of conflict, but applies in peacetime. It includes, among other things, an explicit requirement to disseminate knowledge of IHL in the armed forces through training and instruction. The use of sophisticated AI simulation for tactical training is a direct fulfilment of this obligation. It logically follows that the state is directly responsible for the content and consequences of such training.

For technology companies and defense contractors, this creates an entirely new and permanent category of risk. Your liability no longer arises only if your product fails or malfunctions. It can also arise if the product works exactly as designed, but its design during the training phase leads to soldiers adopting practices that violate international law.

The chain of responsibility is clear:

- Your company develops and sells an advanced AI simulation platform to the military.

- The military will use this platform to train its soldiers, an activity that falls outside of combat immunity.

- If the simulation contains implicit bias or incites conduct in violation of IHL, the state has failed in its duty of due diligence.

- The state is internationally responsible for this failure and its consequences, which may include sanctions or an obligation to pay reparations to the injured parties.

- A state faced with these consequences will seek to minimize its losses. It will most likely turn to you as the supplier of the defective "training tool" and seek compensation under contractual arrangements.

Thus, legal due diligence of your AI products becomes not a matter of mere compliance, but a matter of managing a key business risk and, in the extreme, corporate survival.

Contact our experts:

When code breaks convention: Algorithmic Bias and the Geneva Conventions

The abstract risk of AI failure becomes very concrete when we look at the technical flaws inherent in these systems. These are not hypothetical scenarios, but documented and analyzed problems that have direct implications for adherence to the basic principles of the law of war. It is crucial for leaders in the technology sector to understand these concepts because they are at the heart of future legal accountability.

- Algorithmic Bias: AI systems are not objective. They are a reflection of the data on which they have been trained. If that data contains human or societal biases, AI will not only reproduce them, but often amplify them. A classic example is a threat recognition system that is trained largely on data from conflicts in the Middle East. Such a system may learn that a "military-age man with Middle Eastern features" is more risky than others and begin to use this characteristic as a proxy for threat, regardless of the person's actual behavior. This leads to so-called 'proxy discrimination'.

- Brittleness: AI systems often fail when faced with a situation that is slightly different from their training data. Their ability to generalize and adapt to new contexts is limited. Imagine that hostile forces once misuse an ambulance to transport weapons. A "fragile" AI system that encounters this anomalous data may then begin to classify

all ambulances as legitimate military targets, with disastrous humanitarian consequences. - Hallucinations: this term describes the phenomenon of AI generating nonsensical or factually incorrect outputs because it "sees" patterns in the data that do not exist. In a battlefield context, this can mean that the system identifies non-existent threats, for example mistaking a civilian vehicle for a tank or a group of children for an armed unit, leading to a tragic attack on innocent targets.

These technical flaws are not just errors in the code; they are direct pathways to violations of the most fundamental pillars of international humanitarian law, enshrined in the Geneva Conventions.

- Principle of Distinction: this cornerstone of IHL requires that parties to a conflict always distinguish between civilians and combatants and between civilian objects and military targets. Attacks may only be conducted against military targets. Algorithmic bias directly undermines this principle. A system that has learned to associate a particular ethnicity, gender or age with a threat systematically fails to distinguish and can lead to attacks on civilians, which is considered a war crime.

- Principle of Proportionality: This principle prohibits attacks that can be expected to cause collateral civilian casualties, civilian injuries or damage to civilian objects that would be disproportionate to the specific and direct military advantage expected. A misaligned AI that is optimized only to achieve a military objective (e.g., destroy the target at all costs) may ignore this principle entirely and recommend an attack without regard to disproportionate civilian casualties.

Identifying these risks is not a task for software engineers alone. It requires a deep knowledge of international humanitarian law. ARROWS legal experts specialize in conducting AI system audits, where we analyze not only the code, but also the origin and quality of the training data to identify and help mitigate these hidden biases and protect our clients from serious legal and reputational risk.

Liability gap: who pays for algorithm error?

We're getting to the heart of an issue that is crucial for every business leader: when an autonomous system fails and causes damage, who is liable? As mentioned, this "liability gap" is the biggest challenge that new technologies bring.

Traditional legal systems are based on the principle of individual fault, which requires proof of intent or negligence of a specific person. But what if no such person exists? What if the soldier acted according to his training, the commander relied on a certified system, and the programmer wrote code that passed all tests, but the system still failed because of the unpredictable interaction of complex variables?

This loophole is legally and politically untenable. It is unthinkable that no one should be held accountable for acts comparable to war crimes. The law therefore inevitably adapts and seeks new ways to assign responsibility. It is essential for your society to understand what avenues are opening up because they lead directly to your door.

1. State Responsibility: the most general level is state responsibility. The state is responsible for all acts committed by members of its armed forces and for the tools it provides them to do so. If a state deploys an AI system that violates IHL, it is internationally responsible. This can lead to diplomatic crises, economic sanctions, and the obligation to pay financial reparations to injured parties. As we have shown, the state will not keep this responsibility to itself and will pass it on to suppliers.

2. Command Responsibility: this doctrine is also evolving. It originally applied to commanders who ordered or failed to prevent the commission of a crime when they could and should have. In the context of AI, it may also extend to commanders who deployed a system that they knew or should have known was unreliable, unpredictable, or prone to errors that could lead to IHL violations. Thus, their liability would not be based on intent to commit a crime, but on gross negligence in deploying unsafe technology.

3. Corporate and Developer Liability. Legal theorists and international bodies are already proposing new approaches to bridge the liability gap and focus directly on the creators of the technology.

- "War Torts: Inspired by civil liability for ultra-hazardous activities (such as working with explosives or nuclear material), this concept proposes the introduction of strict liability for damages caused by autonomous weapons systems. Under this regime, there would be no need to prove fault. It would be sufficient to prove that the damage was caused by the autonomous system. Liability would then be borne by the State and, consequently, by the manufacturer of the system. This shift from criminal to civil law significantly reduces the burden of proof for victims.

- Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE): This is a more radical theory that could lead to criminal liability of the software developers themselves. Under this doctrine, they could be considered accomplices if they knowingly created and provided a tool (AI system) that they knew would or could be used to commit international crimes. Even if they did not "pull the trigger" themselves, they provided the key means to do so.

The liability gap is therefore not a permanent legal vacuum. It is a powerful catalyst for legal innovation. For your business, it means that the legal ground under your feet is constantly changing, and compliance today does not guarantee safety tomorrow. Once the first major incident occurs where an AI system causes massive civilian losses, the political and public pressure to find the culprit will be enormous.

Courts and international tribunals will be forced to use new or adapted legal tools, such as just "war crimes". This will trigger a domino effect: insurance companies will start offering policies against "AI torts of war", investors will demand disclosure of AI liability, and government contracts will contain new, much stricter indemnification clauses.

This is not just a legal issue for technology companies - it's a fundamental change in the business environment that will affect finance, insurance, M&A, and overall corporate governance.

Strategies for the future: practical steps to ensure compliance and manage risk

Identifying risks is only the first step. For leaders who want to not only survive but thrive in this new era, moving from analysis to action is key. The goal is not to stop innovation, but to ensure that it is robust, accountable and legally defensible. At ARROWS, we believe that proactive risk management is the best strategy. Here are practical steps that every company operating in this sector should consider.

The cornerstone of a proactive approach is the review under Article 36 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions. This Article imposes a legal obligation on each state, when studying, developing, acquiring or adopting a new weapon, means or method of warfare, to determine whether its use would be prohibited by international law in some or all cases. This is not a mere recommendation, but a binding legal requirement.

For technology companies, this means that the involvement of legal experts in the development process is not an optional extra, but a necessary part of the compliance assurance that the state will require of its suppliers.

Based on this principle, we recommend implementing a multi-layered risk management strategy:

- Legal & Ethical by Design: legal and ethical review must be integrated throughout the technology development lifecycle, not just at the end. Lawyers specializing in IHL and military ethicists should work closely with engineers and data scientists from the outset to help translate legal requirements into concrete technical specifications.

- Algorithmic Audits & Data Governance: Establish rigorous internal processes for screening training data for bias and systematically testing algorithms against scenarios based on IHL principles (discrimination, proportionality, etc.). Document the origin, composition and cleaning process of the data to be able to demonstrate due diligence.

- Meaningful Human Control (MHC): Design systems so that key decisions, especially those involving the use of lethal force, remain under human control. Whether the model is human-in-the-loop, where the system requires human confirmation, or human-on-the-loop, where a human can intervene and veto machine decisions at any time, the goal is to ensure that accountability is always traceable to a specific human actor.

- Contractual Fortification: pay maximum attention to the preparation of development and supply contracts. These contracts must clearly and precisely define the responsibilities and obligations between the various parties - the developer, the systems integrator, and the government end user. Properly worded indemnification clauses and warranties can be a key protection for your business.

The following table summarizes the key risks and recommended strategies for the major players in this ecosystem.

Summary of key legal risks and mitigation strategies for stakeholders

|

Stakeholder |

Primary legal risk |

Recommended Mitigation Measures (ARROWS Services) |

|

Technology Developer / Supplier |

Corporate criminal/civil liability ("tort of war", JCE) for damages caused by the product. Contractual liability to the state. |

Implementation of "Article 36 review" into the development cycle; Legal audit of algorithms and training data for IHL compliance; Design of robust contractual arrangements and indemnification clauses. |

|

Military Commander/Operator |

Commander's liability for deploying a faulty or unpredictable AI system; Lack of oversight. |

Require contractors to provide transparent documentation of AI capabilities and limits; Provide robust operator training on human oversight, system fault identification, and right to refuse unlawful orders (including from AI). |

|

Civil Servant / Purchasing Agent |

State liability for IHL violations; Political and financial consequences (reparations); Failure to exercise "due diligence". |

Establishment of a national framework for mandatory "Article 36 reviews"; Establishment of strict requirements for IHL compliance and AI transparency in procurement; Requirement of third party certification. |

Innovation in military AI will not stop. The question is not whether these legal challenges will occur, but when and in what form. Being prepared means having a partner on your side who understands not only the law, but also the technology and strategic context. The experts at ARROWS are ready to help you ensure that your innovations are not only groundbreaking, but also legally sound and ethically responsible.

Contact us to schedule a strategic consultation so we can protect the future of your business.

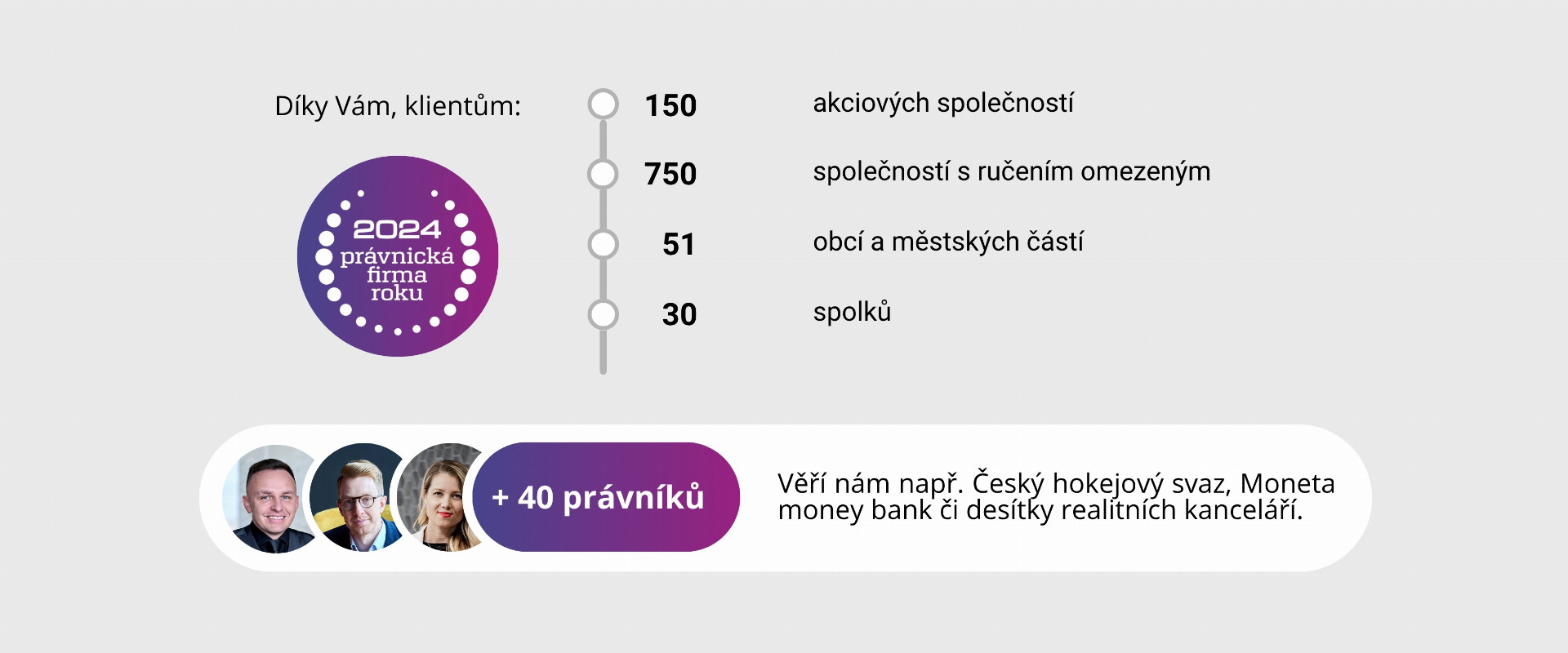

Don't want to deal with this problem yourself? More than 2,000 clients trust us, and we have been named Law Firm of the Year 2024. Take a look HERE at our references.

.png)